We've all been there. Staring at a tricky passage, fingers tensed, mind laser-focused on that next note or chord. We tense, we lunge, we grit our teeth... and often, we stumble. OK, slight overkill, but you get the idea. The note might be hit (eventually!), but it sounds forced, the rhythm wobbles, and our shoulders feel like they're up around our ears.

We spend hours drilling scales and chord shapes, focusing on the notes themselves. We aim for them, we land on them, and we hold them. But what about the journey between them?

As an Alexander Technique teacher, I see this regularly, the guitarist who is so focused on the destination (the note) that they forget about the journey (how they get there). In Alexander terms, this is the classic trap of "End-Gaining."

The End-Gaining Trap: Aiming for the Bullseye

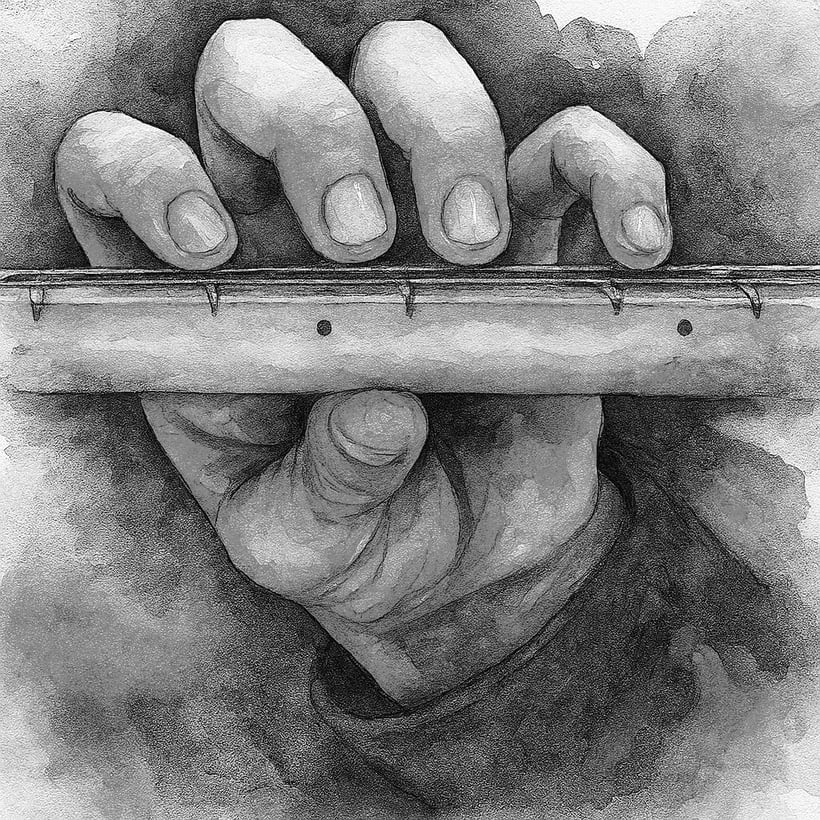

Most of us are natural and inveterate "end-gainers." We fixate on the result – hitting that high C on the 20th fret, nailing that Bm11 chord change on the beat. Our entire system gears up for that specific destination. We contract muscles unnecessarily, hold our breath, and often pull our head down towards the fingerboard in a desperate attempt to "aim" better.

End-gaining is fixating on a goal without paying attention to the quality of the process. On the guitar, it looks something like this:

- Staring intently at the fretboard, mentally yelling "GET TO THE HIGH C!"

- Gripping the neck with a death grip for "security."

- Locking your shoulders and holding your breath as you make a difficult reach.

- Sacrificing tone, rhythm, and ease just to arrive at the note, no matter the cost.

The result? Tense, choppy, and unreliable playing. It’s the musical equivalent of a car journey where you only care about the destination, so you slam on the accelerator and then jam on the brakes at every red light. It’s inefficient, stressful, and hard on the machinery (in this case, your body).

The Musical Alternative: The "Means-Whereby"

The Alexander Technique teaches us to shift our focus from the end (the note/chord) to the means-whereby we achieve it. The process, the journey, the quality of movement in between. This is revolutionary for guitar playing.

Think about it, anyone can play one note fast. The true challenge of technique is getting gracefully from one note to the next. And that means your rhythmic skills, the most fundamental aspect of music, are also to be found in the transitions.

The space between the notes isn't empty, it's where your technique and rhythm lives. It's where your fingers find their new positions, your pick changes direction, and your body organizes itself for the next move. When you focus on the means-whereby, you stop treating the notes as isolated targets and start treating music as a continuous, flowing stream of movement.

: Instead of forcing your fingers with mental commands, use Alexander-style "." These are gentle thoughts that encourage ease and coordination and prioritises your general functioning, which always precedes specific functioning: "Neck free, head forward and up, shoulders widening, arms releasing away from my back." As you initiate the transition, think the movement path with ease, rather than focusing solely on the destination fret. Direct your whole self, not just your fingertip.

- The Transition Is the Technique: Instead of seeing the space between notes as a problem to be rushed through, recognize it as the very ground where good technique is built. How you release the pressure from one finger, how your hand floats (rather than crashes) to the next position, how your arm guides the shift – this is your technique manifesting.

- "Up and Out," Not "Down and In": When end-gaining, we often pull our head down and contract our torso, collapsing onto the guitar. Alexander principles encourage maintaining an easy, upwardly mobile poise. Think of your head leading your spine upwards, allowing your shoulders and arms to remain free. This creates space for your arms and fingers to move with greater ease and coordination during transitions.

- Inhibition: Pausing the Panic: Before lunging for that next chord, practice a moment of "inhibition." Briefly pause your habitual reaction (the tension, the rushing). Consciously choose not to react with your usual tightening. This creates a window to direct yourself differently.

- Direction: Guiding the Movement: Instead of forcing your fingers with mental commands, use Alexander-style "directions." These are gentle thoughts that encourage ease and coordination and prioritises your general functioning, which always precedes specific functioning: "Let your neck be free, to let your head go forward and up, to let your back lengthen and widen". The most important word in that phrase is "let", it's a reminder of what not to do! And for clarity, the "forward" is the natural rotation forward of the head over the atlanto-occiptal joint. The natural balance of the head on the spine. As you initiate the transition, think through the movement path with ease, rather than focusing solely on the destination fret. Direct your whole self, not just your fingertip.

- The Power of Release: Good transitions rely as much on letting go of the previous note as they do on preparing for the next one. Is your left hand finger still clamped down hard after the note is played? Is your pick hand tensed in anticipation? Practice consciously releasing unnecessary tension immediately after a note sounds, allowing your hand and arm to regain freedom before the next movement begins.

Another way of thinking about this is to play the music, not the notes.

Practical Takeaways for Your Practice

- The "One Note Game": Play a single note. Focus entirely on the quality of releasing it by emptying your intention from your fingers, letting the string push the finger back up like a trampoline. Find freedom returning to the hand, arm and shoulders. Then, consciously choose how you move to the next note. Repeat slowly.

- Slow Motion Transitions: Practice only the movement between two notes or chords, incredibly slowly. Choose a problematic transition, perhaps moving from an open C major to an F barre chord. Play the C chord, and then stop. Before you move, bring your awareness to the transition itself. Pay attention to:

-

- Where does tension creep in first (jaw? neck? shoulder? forearm? specific finger?)

- Is your breath flowing?

- Is your head balancing freely, or are you pulling it down?

- Can you make the movement smoother, lighter, with less effort?

- Is there a "pivot" finger that can remain in place through the transition into the next chord.

- Can you have the fingering of the next chord in place, lightly touching the strings, before you apply pressure to the strings.

- Think "Up" During Shifts: Especially during position shifts or large stretches, consciously think of your head leading upwards as you move your hand. This counteracts the collapsing tendency.

- Right Hand Too! This isn't just for the fretting hand. Picking hand fluidity, the transition from one string to the next, the release after a stroke, the preparation for the next, is equally crucial. I like to define a full pick stroke as starting from light contact with a string, and ending in light contact with the next string to be played. This is especially helpful when crossing strings.

- Non-Doing: Often, better transitions come from removing excess effort rather than adding more force. Can you make that chord change with less muscular work? Trust the instrument and the support of gravity more.

Why Bother? The Payoff

When you shift your attention from end-gaining to the means-whereby, a remarkable things happen. Your technique stops being a series of frantic landings and starts becoming a single, integrated dance.

- Improved Coordination: Good coordination is the hallmark of the means-whereby

- Effortless Speed: Fluidity, not force, creates real speed. Unforced movement is inherently faster than tense, frantic movement.

- Consistency: Your consistency improves because you're programming the pathway, not just the endpoint.

- Improved Tone: Notes speak more clearly when your hands arrive without tension. Chords sound fuller when fingers land together without a crunch.

- Musical Phrasing: Smooth transitions are the essence of legato and graceful phrasing. Music flows through the transitions. Your musicality blossoms because the notes are connected with intention and grace, not desperation.

- Reduced Fatigue & Injury Risk: Eliminating the constant "micro-tensions" during transitions saves enormous energy and reduces strain on muscles and tendons. You prevent injury because you're replacing strain with intelligent, conscious use.

- Presence: You become more aware of your whole self in the act of playing, leading to greater control and musical expression.

Remember, anyone can play a single note fast. The guitarist who masters the transitions, with awareness, release, and coordinated ease, is the one who truly makes music. Stop aiming at the notes. Start paying attention to the graceful journey between them. That's where your most beautiful playing lives. Stop aiming, and start traveling.

This may be construed as a little "Zen", and that's fine. I could have easily titled my book Effortless Guitar, as Zen Guitar (although there's already a book of that name), but I wanted to provide a more practical and down to earth guide. A more philosophical view can, though, be just as practical.

Effortless Guitar, published by GuitarVivo available from Amazon and Audible.

Write a comment

Anthony Smith (Tuesday, 28 October 2025 11:47)

Parkinson’s disease runs in my family, both my father and uncle passed away from it. So, when I was diagnosed, I was scared but determined not to follow the same path. For years, I tried different hospital treatments and therapies, but my condition only worsened. That changed when my neurologist recommended EarthCure Herbal Clinic (www . earthcureherbalclinic . com). I decided to try their natural treatment, and within a couple of months, my symptoms started disappearing. It’s now been three years, and I’ve had no signs of Parkinson’s since. I’m truly grateful to my neurologist and to EarthCure Herbal Clinic for giving me hope and health again. I wholeheartedly recommend them to anyone seeking help for Parkinson’s disease.