DEFINING THE ALEXANDER TECHNIQUE Tim Soar © 1999

16. Monkey

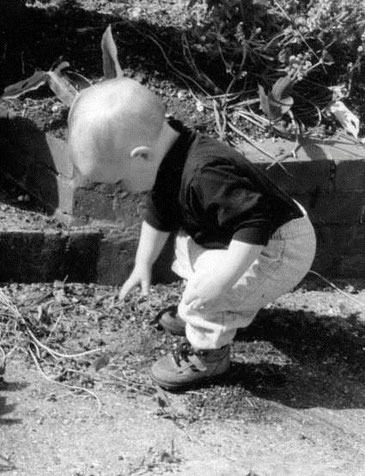

If a small child picks up an object from the floor, he will invariably adopt a partial squat, an attitude known in the Alexander Technique as a monkey –folding at the hips, knees and ankles and maintaining the integrity of the head/ neck/back relationship – in order to reach the floor.

The fact that this pattern of movement is so inaccessible to most adults is merely further evidence of the extent to which we interfere with our natural poise and balance. Alexander realised that this simple movement can be used both as an accurate indicator of the quality of a person’s postural coordination and as a procedure through which to improve that coordination. This is, of course, part of the idea of working on the chair, and monkey can add an extra dimension to this process of postural refinement.

There are, perhaps, three principal benefits to be gained from learning and practising monkey.

- I often introduce monkey to my students whilst working on the chair as a way of providing more “thinking time” during the movement between sitting and standing (or vice versa). If you stop in a monkey halfway through the movement it is often possible to notice, and release, stiffening and distortion which you might otherwise miss. Practising in this way will, in time, enable you to become more self-aware during the movement itself.

- Using monkey is the most natural way to bring your hands or head nearer to the ground in order reach or see something (pick up a cat or write a shopping list resting on a table whilst standing). Even practised imperfectly monkey represents a significant improvement on the contortions most people perform when “bending”. Done well, monkey provides an attitude of immense strength and stability combined with great mobility (modified monkey-like stances are used in all the martial arts, for example).

- A really skilful monkey actively encourages the primary control to work well, opening the back out, stimulating the breathing and integrating the limbs with the core of the body. Whilst it is obviously easiest to learn and explore monkey in its most basic and symmetrical form to begin with, it is important to realise that monkey should not become a stereotyped or mechanical pose but rather an easy and flexible use of the head, neck, back and legs which can provide small movements, and adjustments of balance and weight, not only up and down but also from side to side and forwards and backwards (the “lunge” in fencing is one example).

Like everything in the Alexander Technique, the key to good monkeys is inhibition – standing with the legs bent does not constitute a monkey; standing with the legs bent without stiffening the

neck or jamming the head down onto the spine, without clenching the legs or restricting the breathing, does.